MARINE life

christmas island

Discover an enthralling destination beneath the surface where a vibrant array of aquatic animals are your guide.

Australia boasts its own underwater wonder akin to the Galapagos Islands, known for its vast, remote, and largely unexplored marine landscapes. At twice the size of the Great Barrier Reef and more than three times the size of Great Britain, the waters around Christmas Island have been officially recognised as part of Australia’s Marine Parks. Encompassing 744,000 square kilometers, the Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Island Marine Parks are celebrated jewels within the Indian Ocean Territories, hosting marine species unique to this part of the world.

The marine parks lie at a meeting point of Indian and Pacific Ocean currents. They are places where unique marine life lives and continues to evolve – a natural laboratory for understanding oceanic evolutionary processes. They are important habitats for sea turtles, seabirds, whale sharks, coral reef species, oceanic fish and the famous Christmas Island Red Crab.

Established in March 2022, the marine parks aim to safeguard the distinct marine ecosystems of Australia’s Indian Ocean Territories, fostering environmental conservation. This initiative builds upon the conservation efforts previously undertaken by the Christmas Island National Park and Pulu Keeling National Park, further protecting the unique biodiversity of these islands.

For those eager to explore the underwater marvels of Christmas Island, a variety of local tour operators offer immersive experiences like scuba diving, snorkelling, free diving, and fishing. The island’s surrounding narrow fringing reef, home to 88 coral species and over 650 species of fish, sits on the edge of the Java Trench—the Indian Ocean’s deepest point—creating breathtaking steep drop-offs just beyond the reefs. This marine paradise is a testament to the beauty and ecological significance of Christmas Island’s aquatic environments, easily accessible straight from the shore.

MARINE LIFE

CHRISTMAS ISLAND’S UNDERWATER WORLD OF WONDER

Nestled in warm tropical waters, Christmas Island is an underwater paradise, renowned for its crystal-clear visibility and an astonishing variety of marine life. This unique island is the pinnacle of an extinct volcanic system, perched on the brink of the 3000m deep Java Trench. The underwater landscape around Christmas Island is a breathtaking spectacle of nature, featuring dramatic

drop-offs and vibrant reefs adorned with spectacular corals, mysterious caves, and a kaleidoscope of colourful tropical fish.

The island's marine environment offers an underwater haven for divers and snorkelers alike, inviting them to explore its hidden depths where the richness of life and the beauty of the ocean merge into an unforgettable aquatic experience.

THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT

The waters surrounding Christmas Island are a sanctuary for spinner and common dolphins, alongside populations of green turtles that choose the secluded sands of Dolly and Greta beaches for their nesting grounds. The sight of baby green sea turtles emerging from their nests is an incredible experience and a testament to the island's diverse marine habitat.

During the wet season, the island becomes a temporary home to visiting whale sharks, drawn by the perfect feeding conditions and possibly the red crab spawning. This natural spectacle marks the beginning of the wet season, with whale sharks gathering to enrich their diet with crab larvae, highlighting the intricate connections within the marine ecosystem.

The marine environment is also crucial for the survival of Christmas Island's seabirds and land crabs. Endangered species such as Abbott’s booby and the emblematic white tailed tropic bird, rely on these waters for fishing. The island's seabirds, seen skimming the ocean's surface for fish, add to the area's biodiversity.

Land crabs, particularly the famed red crabs, depend on the marine environment for reproduction. Their annual migration from the rainforest to the sea to spawn is a spectacular event that captivates observers, showcasing the profound link between land and sea.

These ecological connections forge a rich and diverse ecosystem on Christmas Island, where the dance of marine and terrestrial life creates a unique and spectacular natural harmony.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND REEF FISH

Christmas Island’s fish community is distinctive because the island is a meeting place for Indian and Pacific Ocean fish species – it’s one of the few locations in the world where Indian and Pacific Ocean fish swim side by side. Some of these species interbreed to produce hybrids. Christmas Island has more hybrid fish than anywhere else in the world, making it a marine hybridization zone of international significance. Around 575 species of fish have been identified from the island's waters and are mostly fish associated with coral reefs.

SURGEONFISH & UNICORNFISH

Surgeonfish are an important herbivore on the reef and are commonly seen grazing in shallow waters, often in schools. They are named for the scalpel-like blades at the base of their tail. These blades can inflict a serious wound if the fish is handled carelessly. Unicornfish are generally found in smaller groups or pairs and many species feed midwater on plankton.

TOADFISH & PUFFERS

These slow moving fish are able to puff themselves up into a ball. This puffing ability, along with their highly toxic flesh and skin, make them unpalatable to predators. They vary in size from 5 to 90 cm, are generally uncommon, occurring singly or in pairs.

DAMSELFISH

Damselfish are probably the most common shallow water fish found on coral reefs with over 300 species found worldwide. The group includes the most famous coral reef fish – the clownfish or anemonefish. There are three species of anemonefish at Christmas Island (among other damselfish species) and they can be seen living safely amongst the tentacles of their host anemone on the reef top and edge between five and 40 m. Damselfish range between 4 and 10cm in length.

HYBRIDS

At least 11 different hybrids have been recorded at Christmas Island. These hybrids are often a result of interbreeding between Indian and Pacific Ocean species. Usually one of the parent species is rare and unable to find a partner, forcing it to mate with the next closest species. On Christmas Island, species of surgeonfish, butterflyfish, angelfish, triggerfish, wrasse and toadfish have been know to produce hybrids. The hybrids are identified by their unique colour patterns, which are a mixture of the two parent species. Hybrids can be seen in the same locations as the parent species and often in the same social groups.

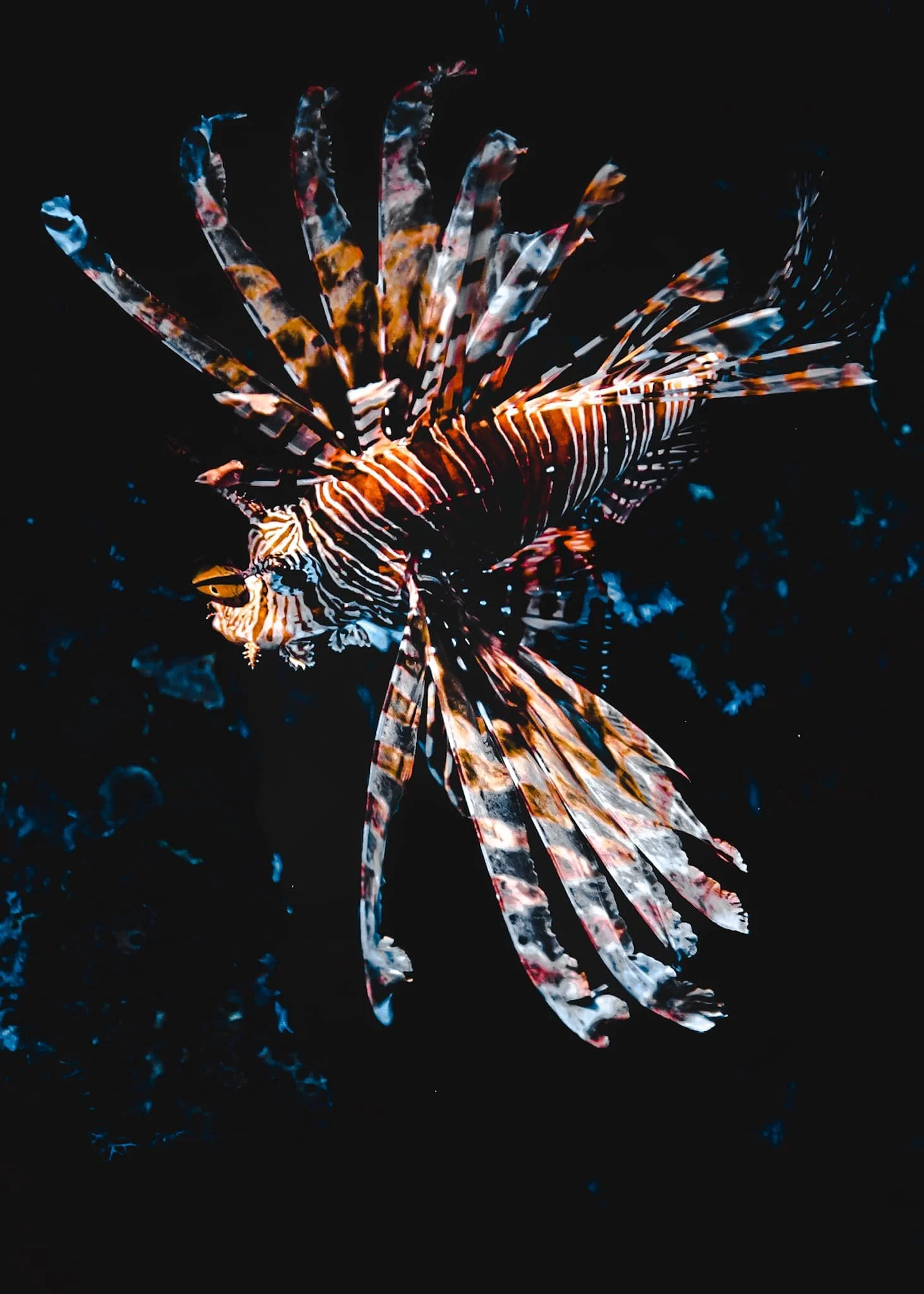

CODS & BASSLETS

This broad group includes small colourful basslets (15 cm) and large predators (up to 2.7 m). The basslets may form harems of one male and many females, or large schools. These vibrantly coloured fish (usually purples, reds and yellows) are abundant on the drop-offs, where they hover above the reef feeding on plankton. The cods and groupers (20-270 cm) are ambush predators that camouflage with the reef and engulf prey such as fish and crabs with their large mouths. They are often spotted or barred.

GOATFISH

These slender cigar-shaped fish are easily recognised by their two barbells (whiskers) situated under the chin. The sensitive barbels are used to sift through the sand and detect prey such as shrimps. Goatfish are commonly between 20 and 40 cm in size and they often have a distinct stripe or spot on the body.

ANGELFISH

These spectacularly coloured fish are highly prized by photographers. Ranging in size from five to 50 cm, they are among the most elaborately patterned fish in the world. Angelfish are distinguished from other fish by a noticeable spine on their lower cheek. The Cocos angelfish is found only at Christmas and Cocos Islands as is the endemic subspecies of the lemonpeel angelfish. Lemonpeel angelfish are common in the shallows at Christmas Island – identify the juveniles by the black spot with a blue margin which fades as they become adult.

MOORISH IDOL

The Moorish idol is a picturesque fish that looks like a butterflyfish but is in a family of its own. It has black, yellow and white vertical stripes with a trailing dorsal filament and is found in the same shallow coral reef habitat as butterflyfish. You may see it on its own, in pairs or in small schools. Look for juveniles sheltering amongst branching corals.

MORAY EELS

Thirty-four species of moray eels have been recorded at Christmas Island all of which come in a variety of colours, shapes and sizes. They are generally found hiding in and around hard corals and can often be seen whilst snorkelling or scuba diving. Some species have blunt teeth which are used for crushing crabs and molluscs while others have sharp, needle-like fangs used more for feeding on prey items such as fish, shrimp and octopus. Moray eels are not normally aggressive however the masked moray eel can be territorial and bite intruders if they come too close.

WRASSES

This is a diverse group that exhibit a range of sizes (5-230 cm), colours and diets. The majestic humphead maori wrasse is the largest member and uses its powerful jaws to crush shellfish or feed on crown-of-thorns starfish. One of the smallest members of this group is the blue and white striped cleaner wrasse, which feeds by eating parasites from other fish that visit the wrasse’s ’cleaning station’. Most wrasses form harems where the largest member of the social group is a brightly coloured male surrounded by dull coloured females.

BUTTERFLYFISH

These are one of the most beautiful groups of fish in the sea. Their posterlike colours and unique patterns make them easy to identify. Typically 8-15 cm in length, butterflyfish can be seen on shallow coral reefs, swimming in pairs and picking at food on the substrate. Some species feed exclusively on corals, while others have a broad diet.

TRIGGERFISH & LEATHERJACKETS

These two closely-related families are distinguished from other fish by the presence of a sturdy dorsal spine that they erect to help wedge themselves into holes when danger approaches. These fish have rough skins and some, such as the clown triggerfish, have vivid colour patterns.

PARROTFISH

Parrotfish are closely related to wrasses but can be distinguished by their fused teeth that look like a parrot’s beak. Usually 20 to 100 cm in length these fish are commonly seen in shallow water grazing on algae. Some species eat corals that they crush with their powerful jaws, returning sediment to the reef in the form of sand. Like wrasses, many parrotfish have a haremic social system with the largest fish being a brightly coloured male and the smaller fish are dull coloured females.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND PELAGICS

Christmas Island’s pelagic (open ocean) species include tunas, wahoo, barracuda, rainbow runners, mackerel scad, sailfishes, marlin, swordfishes and trevallies. Many are fast swimmers, escaping danger by bursts of speed. Many are schooling fish and find added safety by gathering together and swimming about in large numbers. Most pelagic fishes have protective colouration - blue or dark grey above and white or silvery underneath, making them less visible to predators from above or below them.

BARRACUDAS

These pelagic fish are long (up to1.8 m) and have large teeth. Silver in colour with a series of dark bars, they are regularly encountered on the drop-offs where they hunt fish. Larger barracudas are often alone but smaller barracudas will form schools.

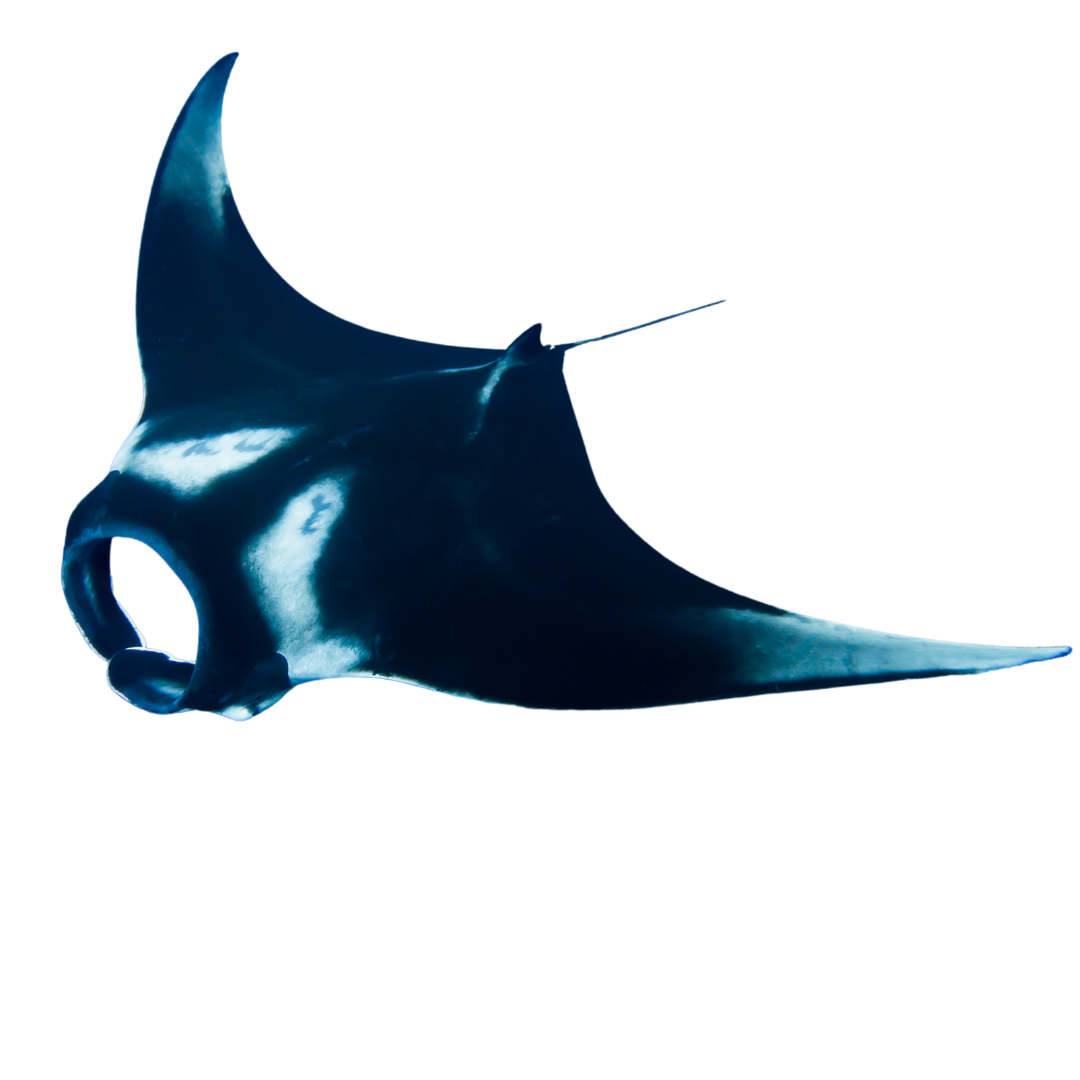

MANTA RAYS

These huge rays cruise the open water in search of tiny plankton to feed on, using their wings to propel themselves through the water - they may have a wingspan over seven metres. Manta rays are usually black all over with white patches and two protruding flaps on either side of the mouth that are used to funnel plankton as they feed. Manta rays can occasionally be seen leaping from the water but are most commonly seen cruising just under the surface, or visiting ‘cleaner stations’ on the reef where cleaner fish remove parasites.

WHALESHARKS

These are the largest fish in the sea, growing up to 18 m in length but are harmless. Every wet season (November to March) they congregate at Christmas Island, with juveniles (3-7 m) the most common. Whale sharks feed primarily on plankton and their arrival at Christmas Island coincides with the annual spawning of red crabs and corals, whose larvae they presumably feed on. Each whale shark has a unique arrangement of white spots that can be used as a visual fingerprint to identify individuals as they travel around the world.

OTHER SHARKS

Several other shark species inhabit Christmas Island’s waters but are relatively uncommon compared to other tropical areas. The most common species that can be seen whilst snorkelling or diving include white tip reef sharks (which grow up to around 2 m) and requiems (often referred to as whalers). Other sharks include the grey reef shark, scalloped hammerhead, silvertip shark and the oceanic whitetip. The tiger shark is the largest shark in Christmas Island’s waters, but is rarely seen.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND INVERTEBRATES

Christmas Island’s dominant group of marine species are its corals, which are tiny animals called polyps that live in colonies. More than 100 species of coral are found in the island’s warm tropical waters, providing habitat for all coral reef species.

HARD (REEF BUILDING) CORALS

Hard corals - also known as stony or true corals - grow by building a chalky limestone case with calcium taken from sea water. Large plate corals, branching corals and encrusting corals are common in Christmas Island’s waters. It is difficult to identify particular species of coral as the shape of a coral colony depends on its environment. A species which grows in a rounded mass in areas with strong waves may produce slender branches in deeper, calmer water. Light level and the amount of sediment in the water also influences coral colony shapes.

SOFT CORALS

Soft corals and sea fans have no hard external skeleton and can also be distinguished from hard corals by their swaying soft bodies. The soft body is defended by chemicals which make the coral toxic and bad tasting to predators. Sea fans (also called gorgonians) are supported by a flexible skeleton made of a substance similar to fingernails, called gorgonin. They generally inhabit vertical reef walls at the outer edge of of coral reef shelves.

MOLLUSCS

Three major molluscs grow on the reefs:

Bivalves - The body of a bivalve shell is flattened and is attached to both its hinged shells. The largest of all bivalves and the easiest to find are the clams.

Gastropods - The most common mollusc, with most of the body typically hidden within its shell, which offers protection from predators.

Cephalopods - Octopi, cuttlefishes, squids and nautiluses are all cephalopods, and with the exception of nautiluses, can expel ink to confuse predators. They are the most highly advanced form of mollusc and the most intelligent invertebrate group. The nautilus is the only cephalopod with a true external shell. The inside of the shell is divided into many gas-filled chambers and buoyancy is controlled by taking in or pumping out water.

ALGAE

There are two kinds of marine plants - algaes (seaweeds) and seagrasses. Coral reefs are 'turfed' with fine hair-like algae which are grazed by many animals. Some red algae form hard pink crusts which cement sand and dead coral together.

SPONGES

Sponges stand out from the reef community with their bright colours and range of shapes. Sponges are filter feeders, taking in water and straining off tiny plants and animals, bacteria and oxygen.

ECHINODERMS

Echinoderms include sea stars, brittle stars, feather stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers. The skins of these creatures are hard plates or spines. Sea urchins are usually nocturnal, spending daylight hours wedged under rocks or in crevices. They are herbivorous and graze on algae on the reef and are in turn eaten by triggerfish and pufferfish.

CRUSTACEANS

Crabs, crayfish and shrimps belong to a group of ten-legged crustaceans called decapods. The banded coral shrimp is one of the best known cleaner shrimp species. They clean parasites and excess mucus off fish.

ANEMONES

A sea anemone is a large polyp. Its mouth is surrounded by feeding tentacles and each one contains stinging cells. These are used to capture the plankton and small creatures the anemone feeds on. Some species have special symbiotic relationships with anemonefish. These fish hide amongst the tentacles of anemones to protect themselves and are not affected by the anemone's sting.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND FRESH WATER SPECIES

The limited availability of permanent, above-ground freshwater sources has restricted the numbers and types of aquatic vertebrates found on Christmas Island, although further study is warranted. At least seven species have been recorded from freshwater environments on the Island, all except one of which are probably introduced.

Only one species, the native brown gudgeon, has been recorded from caves. Those species recorded to date are the Asian bony tongue (Scleropages formosus), brown gudgeon (Eleotris fusca), tilapia (Oreochromis sp.), guppy Anemone (Poecilia reticulata), mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis), swordtail (Xiphophorus maculatus) and 'terrapins' (Class Reptilia). Terrapins occur in the tank at Ross Hill Gardens but they have not been identified.

CHRISTMAS ISLAND TURTLE WATCHING GUIDE

Christmas Island is an incredible destination for turtle watching, offering sanctuary to two endangered species of sea turtles: the green turtles and hawksbill turtles. Turtles can be observed in the island's surrounding waters throughout the year, with green turtles also nesting on the picturesque shores of Dolly and Greta beaches. Remarkably, Christmas Island experiences year-round nesting, a rare phenomenon compared to the seasonal nesting periods observed on the mainland.

To ensure the protection of these magnificent species, a specific code of conduct for watching nesting turtles and hatchlings has been established:

For Nesting Turtles

When looking for turtles, walk along the beach near the water just below the high tide mark. This allows the tide to wash your footprints away.

Avoid excess noise and sudden movement at all times.

Do not use powerful torches – your light should be no more than three watts and protected with a red filter (a couple of layers of red cellophane will do). Never shine lights directly on turtles.

When you encounter a turtle, stop and stay at least 15m away. Position yourself behind the turtle and stay low by sitting, crouching or lying on the sand. You may crawl up behind a nesting turtle on your stomach, but do not approach any closer than 15 m.

Be patient. The nesting process can take up to 40 minutes as the turtle may abandon the nest and dig another one for a variety of reasons. Wait until a turtle has started laying her eggs before moving any closer. She will be quite still when laying eggs – if sand is spraying or she is using her front flippers, she is not yet laying. It may take a mother 10–20 minutes to lay her eggs.

A maximum of three people at once may move closer to a turtle once she is laying, staying at least 2 m away at all times.

Give the turtle enough space to camouflage the nest, which may take 20–40 minutes. Remain at least 2 m away while she is doing this.

Let the turtle return to the ocean without interruption. Stay at least 2 m away at all times, and don’t get between the turtle and the ocean. It may take her 5–10 minutes to reach the ocean.

For Watching Hatchlings:

Stand back from the nest to avoid compacting the sand.

Do not use any lights – they will disorient the hatchlings.

Do not get between the hatchlings and the ocean.

Let hatchlings make their own way down the beach. Hatchlings can get stuck in footprints, so stand to the side of their path rather than walking across it.

Adhering to these guidelines ensures a respectful observation of these endangered species, allowing them to thrive and continue their life cycle on Christmas Island. It's an opportunity for families to engage with nature responsibly, fostering a deep appreciation for wildlife conservation.